There are many NGOs, both national and international, that address land issues. They often focus on advocacy work, research related to land grabs, documentation and resolution of land-related conflicts, large-scale land acquisitions, government and military interaction with ethnic populations, forest degradation and illegal logging, and conservation issues. This work is essential for taking land issues forward in Myanmar. However, the nature of these engagements does not always enable collaborative work with public institutions, and sometimes results in confrontational positions with policy decision-makers.

Although major improvements were achieved over the last 10 years, Myanmar continues to have high levels of malnutrition. The phenomenon—of high stunting and anemia rates, overall malnutrition, an unbalanced and rice-dominant diet, and a focus on the development of the rice sector—is one that can be seen across Southeast Asia, similarly occurring in countries like Laos and Cambodia. So, the question becomes how these countries can create an enabling environment for producing and making available the necessary ingredients for a more diversified and nutrient rich diet.

It now seems possible that by century-end the largest sector of acknowledged property worldwide will be community-owned and governed.

The 15th Free Land Camp (Terra Livre, or ATL for its Portuguese acronym) brought 3,000 Indigenous Peoples and their allies together from all regions of the country at a massive encampment in Brasilia to call for justice for indigenous communities. Participants used the gathering—one of the largest ever—to create and present a unified political agenda before the Brazilian government.

The theme of this year’s UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues was “Indigenous Peoples’ collective rights to lands, territories, and resources.” Indigenous leaders from across the globe noted the crucial role that secure rights play in their lives and livelihoods, and in the advancement of sustainable development and climate change mitigation.

In just 29 months, the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of the Archipelago, or AMAN, advanced community tenure security over 1.5 million hectares of land.

More than 4,300 civil society representatives from 130 countries participated this March in the 62nd Commission on the Status of Women (CSW62)—which focused this year on rural women and girls. Although the Agreed Conclusions adopted by all CSW Member States fell short of what advocates were pushing for, they still represent a shared commitment toward respecting the rights of indigenous and rural women.

President Weah has a choice: be “open for business” without recognizing community land rights and risk a backslide into conflict and insecurity or to move towards a new model by prioritizing the land rights of the people who voted him into office and consolidate peace and sustainable development in Liberia.

A new analysis of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Mai-Ndombe province finds REDD+ investments in the region are moving forward without clear recognition of the land rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. The findings come at a crucial time, as a decision on future investment by the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility is imminent.

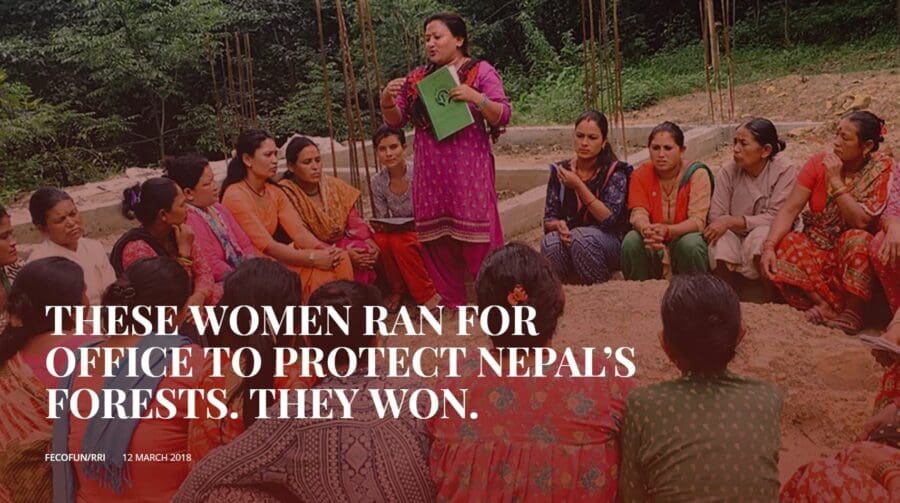

As Nepal wrote a new constitution and laid out guidelines for three tiers of elections, community forest users worried that the new government would leave little room for the voices of traditionally marginalized groups, like rural women and Dalits, a historically persecuted community in Nepal and India. The power to sit at the bargaining table and make important policy decisions, they agreed, had to come from adequate representation, particularly at the local government level.

That’s why women leaders and activists at a civil society organization called FECOFUN decided to run for office.

Indonesia faces a deforestation crisis: an estimated 55 percent of forests located in concession areas were lost over a period of 15 years (2000-2015), with an estimated total loss of more than 6.7 million hectares within and outside of concession areas. The country has been losing its forests at a rapid rate for decades, and in turn, adat and local communities’ livelihoods are under threat, and the wildlife and plant diversity in their traditional territories is being lost….

View the full photo essay here.

We asked six experts about the biggest opportunities, moments, and potential catalysts for change they see for community land rights in 2018. Here’s what they had to say.

New data gathered from Afro-descendant community councils and state records reveal that the Colombian government has failed to address 271 claims for collective Afro-descendant land rights—threatening cultural and environmental sustainability, the rights of Afro-descendant community territories as established by Law 70 of 1993, and the successful implementation of the peace accords. Although all 271 communities have submitted formal applications for collective land titles, the government has largely delayed recognition of their claims—in some cases for over a decade.

There is a real need for community forestry to contribute to reducing emissions while securing immediate community benefits such as livelihoods diversification, climate change adaptation, and employment. These benefits can only become a reality if community tenure, and not simply access and benefits, is secured.

Indigenous and community organizations often find that progressive laws on land tenure do not always translate into progress on the ground. Even in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where forestry laws allow for community ownership and management of land, there are major obstacles hindering the realization of customary forestry rights.

The creation of platforms to acknowledge and address the role of Indigenous Peoples, local communities, and rural women may represent a crucial step toward addressing the disparity between the lands Indigenous Peoples and communities protect and depend on and the legal recognition of their rights. These communities will have a formal platform at future climate talks to exchange knowledge, influence policy, and press for recognition of their rights before world leaders.

Both the conclusions of the conference and the collaboration that went into organizing it attest to the willingness of the current government and civil society to collaborate toward these goals. In the face of globalization and efforts to promote economic growth in Indonesia, full recognition of the land and forest rights of local and adat communities remains of the utmost importance. There is hope that this collaborative effort represents a step in the right direction toward securing the land rights of adat and local communities across Indonesia.

Big transformations are coming to the world of forestry, a sector generally known for being conservative and slow to change.

The community of Santa Clara de Uchunya, in Ucayali, Peru, is fighting back against both land trafficking and human rights abuses in the region.

In Indonesia, large portions of lands and forests have been allocated for industrial plantations and extractive businesses with little respect for the land rights of the Indigenous Peoples and local communities occupying or claiming these areas, despite a 2013 Constitutional Court Ruling stating that customary forests should be returned to their traditional owners.

Millions have learned of the existence of the small island of Barbuda (161 sq. km), through the havoc that Hurricane Irma wreaked on the island, destroying most buildings, roads, water, and power installations. What they may not know is that the less than 2,000 Barbudans collectively own their island; this ownership is under threat, which has been heightened by Hurricane Irma.

On behalf of The World Bank Group, I congratulate the Government of Sweden and the organizers of this event on the launch of the Tenure Facility. Securing indigenous, community, and women’s land rights is fundamental to the Bank’s mission to end extreme poverty and promote shared prosperity.

Tomorrow, October 4, participants from 65 countries—including representatives from Indigenous Peoples, local communities, women’s groups, governments, NGOs, civil society, multilateral banks, and the private sector—are convening in…

For many governments, upholding commitments to demarcate and recognize community lands is both vitally important and no small task—particularly in environments where land commissions face constrained funding, political or economic roadblocks, or other obstacles. After a number of representatives from land commissions in Africa voiced a desire to exchange experiences and learning with their colleagues from across the continent, we joined forces with the African Union’s Land Policy Initiative to hold a three-day workshop in Accra, Ghana.