Spurred by international policy commitments and growing demand from their constituencies, African land institutions are looking to place community land rights at the center of national development agendas.

The work to address the longstanding issue of insecurity around land does not end with legislation. Liberia’s citizens will not gain from the protections of the LRA without implementation. Nor can the government go it alone: given their proximity to communities, history of advocacy on behalf of marginalized groups, and their familiarity with the government’s platform under the new law, civil society organizations are ideal partners for implementation.

Representatives from 13 governmental land agencies in Africa announced today in Antananarivo, Madagascar the launching of the Network of African Land Institutions for Community Land Rights (ALIN) to serve as a platform for exchange and mutual support to advance opportunities to secure indigenous and community land rights across the region.

Cyclone Idai is possibly the worst ever weather disaster to hit the southern hemisphere, and it won’t be the last. If anything, this disaster has brought home the message that disaster preparedness is inadequate. The design and planning of cities and physical infrastructure should be climate-resilient, taking into account the many important ways in which local community rights and capacities, nature, and nature-based solutions contribute to reducing risks and building resilience. This is particularly pressing as climate change heightens the frequency and magnitude of these extreme weather events, exacerbating the vulnerability of millions of Africans.

“They started the project by taking away communities’ land without their consent, using intimidation and all kinds of misplaced government power to evict them from their own customary land,” said Kipalu, who now works for the Rights and Resources Initiative in Washington, D.C.

On September 19, Liberian President George Manneh Weah signed into law the Land Rights Bill (LRB), a landmark piece of legislation that recognizes the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities to their customary lands and gives customary land the same standing as private land in Liberia. This historic victory sets a precedent for land rights recognition in West Africa and can serve as a model for the region and beyond.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Indigenous Peoples, local communities, and rural women have long struggled to have their customary rights to their lands and forests formally recognized—but a breakthrough in one province shows that this could be changing at a pivotal moment.

Could the tide by turning for one of the continent’s trickiest issues – land rights? In Tunisia, President Essebsi has announced plans to submit a draft bill to parliament that would give women the same inheritance rights as men. Wafa Ben-Hassine, a lawyer and human rights advocate welcomed the news. However, she stressed that for real change to occur, the existing laws need to be implemented effectively. Jenna Di Paolo Colley from the US-based campaign group, Rights and Resources says the inability of local, indigenous populations to defend what’s traditionally been theirs is a basic obstacle to development.

Recent research by the Rights and Resources Initiative demonstrated that the DRC’s first REDD+ initiatives in Mai-Ndombe province do not adequately respect the rights of local peoples. What is more, they are actually failing to protect their forests.

Civil society organizations and communities affected by oil palm concessions across Liberia have grouped themselves in addressing urgent issues in the oil palm sector, demanding more access to mechanisms that can make concessionaires more accountable in line with laws and regulations.

Land rights is emerging as a big issue in the UN’s REDD+ programme to reduce deforestation, with concern focused on a tract of 9.8 million forested hectares in the Mai-Ndombe province in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

The forests of Mai-Ndombe (“black water” in Lingala) are rich in rare and precious woods (red wood, black wood, blue wood, tola, kambala, lifake, among others). It is also home to about 7,500 bonobos, an endangered primate and the closest cousin to humans of all species, sharing 98 percent of our genes, according to the WWF.

The forests constitute a vital platform providing livelihoods for some 73,000 indigenous individuals, mostly Batwa (Pygmies), who live here alongside the province’s 1.8 million population, many of whom with no secure land rights.

In a new study released today, researchers say they have identified significant flaws in ambitious forest preservation projects underway in a densely-forested region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where a decision on future investment by the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) is imminent. The DRC province of Mai-Ndombe has been a testing ground for international climate schemes designed to halt forest destruction while benefiting indigenous and other local peoples who depend on forests for their food and incomes, with US$90 million already dispersed or committed for climate finance in the province.

A new analysis of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Mai-Ndombe province finds REDD+ investments in the region are moving forward without clear recognition of the land rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. The findings come at a crucial time, as a decision on future investment by the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility is imminent.

Given that the 1989-2003 civil wars were in part driven by disputes over land and resources, observers are worried what the future holds as a UN peacekeeping mission prepares to leave Liberia in March.

We asked six experts about the biggest opportunities, moments, and potential catalysts for change they see for community land rights in 2018. Here’s what they had to say.

There is a real need for community forestry to contribute to reducing emissions while securing immediate community benefits such as livelihoods diversification, climate change adaptation, and employment. These benefits can only become a reality if community tenure, and not simply access and benefits, is secured.

Indigenous and community organizations often find that progressive laws on land tenure do not always translate into progress on the ground. Even in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where forestry laws allow for community ownership and management of land, there are major obstacles hindering the realization of customary forestry rights.

For many governments, upholding commitments to demarcate and recognize community lands is both vitally important and no small task—particularly in environments where land commissions face constrained funding, political or economic roadblocks, or other obstacles. After a number of representatives from land commissions in Africa voiced a desire to exchange experiences and learning with their colleagues from across the continent, we joined forces with the African Union’s Land Policy Initiative to hold a three-day workshop in Accra, Ghana.

Over the last two decades, companies in search of vast tracts of available land for agriculture, mining, and other uses have increasingly turned to rural Asia and Africa. From 2008 to 2010, between 51 and 63 million hectares of land were acquired on the African continent through such large-scale land acquisitions (LSLAs). And while the repercussions of LSLAs affect entire communities, women suffer the most.

Women living in forest communities play a crucial role in climate change mitigation and economic development in low- and middle-income countries.

In Liberia, the promise of Africa’s first female president has fallen short: across the country, community and rural women have been cut off from the decision-making processes that affect them. Many are losing the lands and resources they rely on.

Ghana’s forests and the people who depend on them face an illegal logging and mining epidemic.

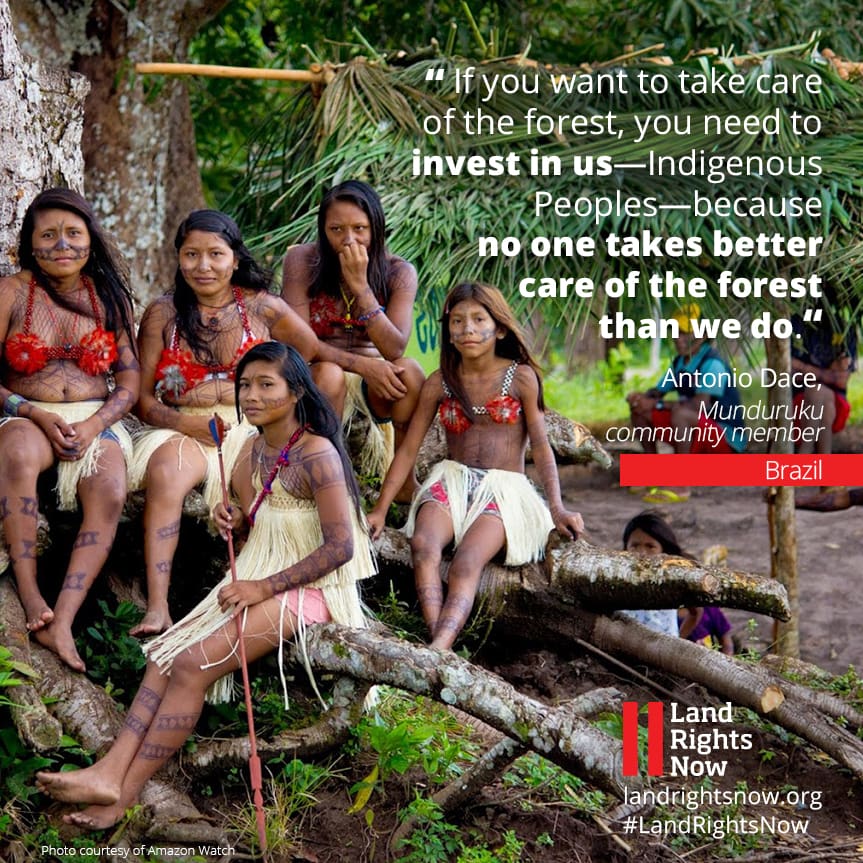

Community advocates in Brazil, Guatemala, Kenya, Taiwan, and 21 other countries call on governments, private sector to recognise that secure land rights are vital to the global struggle against climate change