In welcome news for India’s forest communities, the state of Odisha has approved 14 Community Rights and Community Forest Resource Rights titles for 24 villages in its Nayagarh district, under the country’s 2006 Forest Rights Act. The government’s move to grant these titles is praiseworthy for one key reason: they recognize women’s critical role in protecting community forests.

Secure rights to land are fundamental to enable Indigenous Peoples, and in particular, Indigenous women, to continue their effective stewardship of forests.

Não há empoderamento político sem empoderamento econômico. Esse foi o princípio por trás de uma estratégia de 2019 da Coalizão da América Latina da RRI [Iniciativa de Direitos e Recursos] para analisar sistemas econômicos com base nos próprios conceitos de desenvolvimento das comunidades dentro de seus sistemas de propriedade comum.

There is no political empowerment without economic empowerment. That was the principle behind a 2019 strategy by RRI’s Latin America coalition to analyze economic systems based on communities' own concepts of development within their collective tenure systems.

In Mangkit Village, North of Sulawesi in Indonesia, land was returned to farming families, ending a long struggle between the community and a plantation company. This has crucial implications for the communities’ livelihoods and very survival.

At the most recent Women Deliver conference—the world’s largest gathering on gender equality and the wellbeing of girls and women—experts from across the RRI Coalition had the opportunity to learn from diverse leaders around the world, while also raising awareness of the urgent need to recognize the rights of indigenous, rural, and community women. Here’s what participants said international audiences need to know about the challenges and opportunities facing this unique subset of women.

RRI is thrilled to be participating in the Women Deliver Conference, the world’s largest conference on gender equality and the well-being of girls and women.

Recognizing and securing women’s land and resource rights—in law and practice—benefits women, their communities, and their countries. Strong governance rights for women underpin their ability to participate in decision-making affecting their personal agency and economic security, their children’s future, and the future of the planet. Just a handful of stories from the RRI Coalition demonstrate how, across the world, indigenous and rural women are fighting for their land and resource rights, and using their traditional knowledge and leadership to contribute to myriad global development goals.

Pressures from climate change have worsened poverty, food insecurity, human trafficking, and child marriage, activists argue. For a long time, says Ms. Bandiaky-Badji, people have focused on rural and indigenous women “as victims.”

More than 4,300 civil society representatives from 130 countries participated this March in the 62nd Commission on the Status of Women (CSW62)—which focused this year on rural women and girls. Although the Agreed Conclusions adopted by all CSW Member States fell short of what advocates were pushing for, they still represent a shared commitment toward respecting the rights of indigenous and rural women.

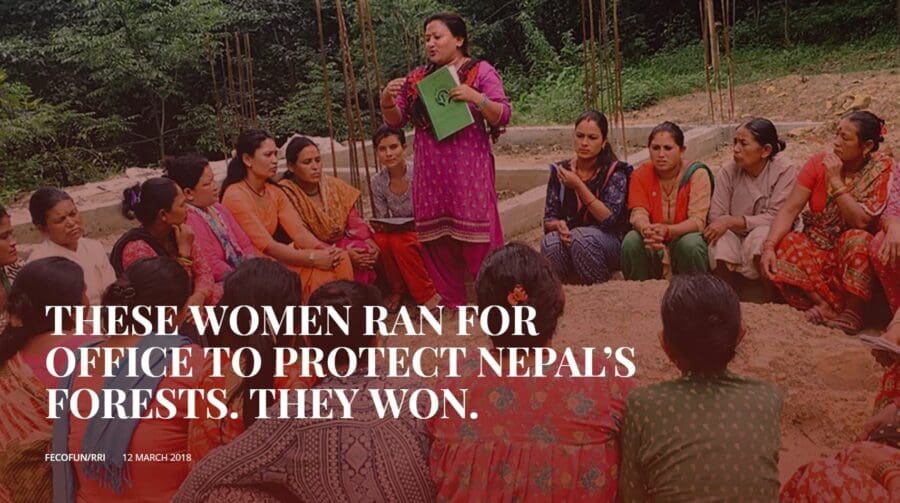

As Nepal wrote a new constitution and laid out guidelines for three tiers of elections, community forest users worried that the new government would leave little room for the voices of traditionally marginalized groups, like rural women and Dalits, a historically persecuted community in Nepal and India. The power to sit at the bargaining table and make important policy decisions, they agreed, had to come from adequate representation, particularly at the local government level.

That’s why women leaders and activists at a civil society organization called FECOFUN decided to run for office.

We asked six experts about the biggest opportunities, moments, and potential catalysts for change they see for community land rights in 2018. Here’s what they had to say.

Arguably the biggest problem facing humanity—climate change—has a surprising solution: legally recognize and enforce the land rights of rural women in customary tenure systems. This November, it is essential that the world’s nations gathering in Bonn for the United Nations’ annual climate change conference (COP23) do not lose sight of this tremendous opportunity.

Tomorrow, October 4, participants from 65 countries—including representatives from Indigenous Peoples, local communities, women’s groups, governments, NGOs, civil society, multilateral banks, and the private sector—are convening in…

Despite growing international commitments to gender equity, there remains a persistent gender gap in women’s political representation, particularly in poor rural and indigenous communities.

RRI Fellow Madhu Sarin has been working on forest tenure reform in India for the last 15 years. In a conversation with RRI, Madhu shares her perspective on what it takes to strengthen women’s land and community forest rights in practice in India, how the country’s Forest Rights Act helped secure women’s land rights, and more.

At a panel event in Lima, Peru, indigenous women advocated for stronger legal protections for indigenous women’s rights to govern their lands and resources.

Over the last two decades, companies in search of vast tracts of available land for agriculture, mining, and other uses have increasingly turned to rural Asia and Africa. From 2008 to 2010, between 51 and 63 million hectares of land were acquired on the African continent through such large-scale land acquisitions (LSLAs). And while the repercussions of LSLAs affect entire communities, women suffer the most.

Inadequate rights for indigenous and rural women are jeopardizing forests and common lands across the globe as demand for land and resources grows.

Women living in forest communities play a crucial role in climate change mitigation and economic development in low- and middle-income countries.

A new analysis from RRI provides an unprecedented assessment of legal frameworks regulating indigenous and rural women’s community forest rights in 30 developing countries comprising 78 percent of the developing world’s forests.

As rural demographics shift, lack of protections for women’s land rights undermines efforts to empower Indigenous Peoples and local communities, conserve tropical forests, and reduce poverty.

In Peru, women are raising their voices to call attention to their unique role as forest managers, and advocate for full participation in land titling projects that would affect them.

Indonesia is one of only two countries assessed that does not guarantee women equal protection under the constitution. Inequitable laws and the expansion of agribusiness threaten the customary practices of many communities who treat women as equals in managing customary lands and resources.