It’s Monday, August 14 of 2023 in Colombia. Cecilia Herrera, a member of the Association of Afro-descendant Women of Northern Cauca (ASOM) sits in a minivan by the window, directly behind the driver. Her fellow passengers include three journalists, one from Mongabay; another from the Colombian newspaper, El Espectador; and a third from the environmental journalism platform, Dialogo Chino.

Also in the minivan are four members of the Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI), including me. Our van is headed to the countryside state of El Refugio, located in Santander de Quilichao, Cauca, where we plan to meet with the leaders of the Association of Afro-descendant communities (called the Black Communities Process or PCN in English) and other members of ASOM.

It is also the day after dissidents of the now defunct guerilla group, Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), detonated a car bomb in the village of Timba in Northern Cauca, killing a police officer. The attack was part of the so-called “pistol plan” in response to a government campaign against drug trafficking. Due to this and previous attacks in this region, Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro is holding a security council in the capital of Cauca, leading to a tense calm in the air.

A week ago, we had planned this day quite differently. The journalists and representatives of ASOM and PCN had expected to visit the community council at La Alsacia, Buenos Aires, which is home to a 22-year-old rights movement by the local Afro-descendant community and its sustainable coffee agriculture and forest conservation initiative. But since La Alsacia is within the township that was attacked, we are now headed for a brief meeting instead in Santander de Quilichao, Cauca.

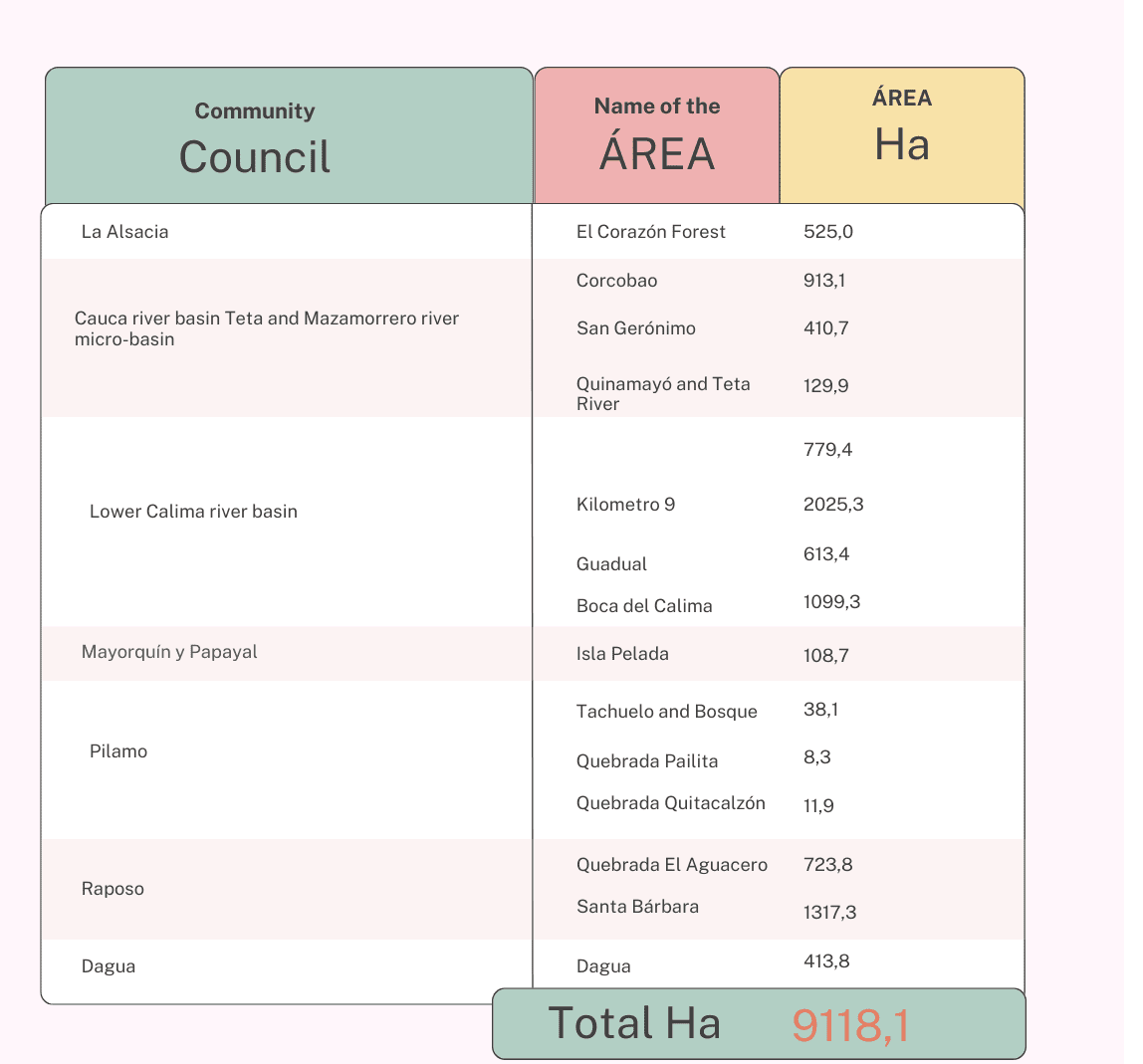

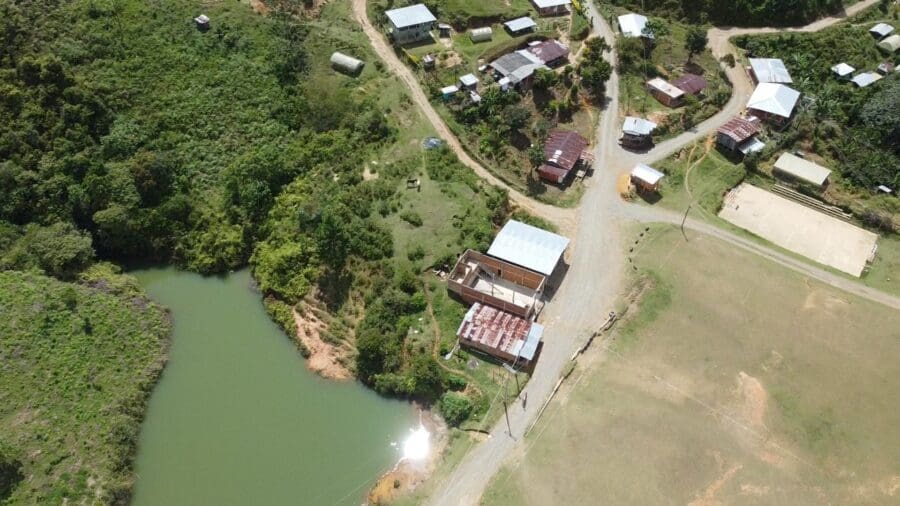

There, we would learn about self-defined rights-based conservation efforts across Northern Cauca and Buenaventura, led by community councils of Afro-descendant Peoples who in 2022 have formalized their traditional conservation systems into 15 community conservation areas in sectors bordering the Yurumanguí River, the Cauca and Calima River basins and the micro-basins of the Mazamorrero, Mayorquín, Payal, Raposo, Dagua and Teta Rivers.

From the road, Cecilia sees a group of children playing in a small creek. One of them emerges from the water, his shorts and T-shirt soaking wet, and climbs onto a high rock, propelling himself back into the water and splashing the other children. “They sure know how to vivir sabroso,” Cecilia says.

In English, vivir sabroso translates loosely as “live well” or “live with flavor”. It was adopted as a campaign slogan by Colombia’s vice president, Francia Márquez, an Afro-descendant woman who began her leadership journey with the same organization that Cecilia belongs to: ASOM. This slogan also represents a philosophy of life for Colombia’s Afro-descendant population. Vivir sabroso does not require wealth, but rather living without fear, with dignity and access to one’s rights and territory. This philosophy has guided the lives and ongoing work of ASOM and PCN leaders amid the ongoing violence between state security forces, illegal gangs, the National Liberation Army (ELN), and FARC dissidents.

The 15 community protected areas created by the region’s Afro-descendant communities are part of the Biogeographic Chocó, a set of territories formed by tropical rainforests, mangroves, coral reefs, and seagrasses. All host ecosystems key to climate change mitigation and adaptation. In fact, more than 25 percent of the region’s animal and plant species are exclusive to this part of the world. However, despite its enormous ecological value, illegal extraction and trade of gold, timber, and fishery resources as well as illegal coca crops and logging for cattle ranching have led to biodiversity loss and weakening of social structures, cultural traditions, and governance by local communities. Afro-descendant Peoples have protected these aspects of their communities for centuries but are now struggling to keep them intact.