“Welcome to the Banten Peasants Movement!”

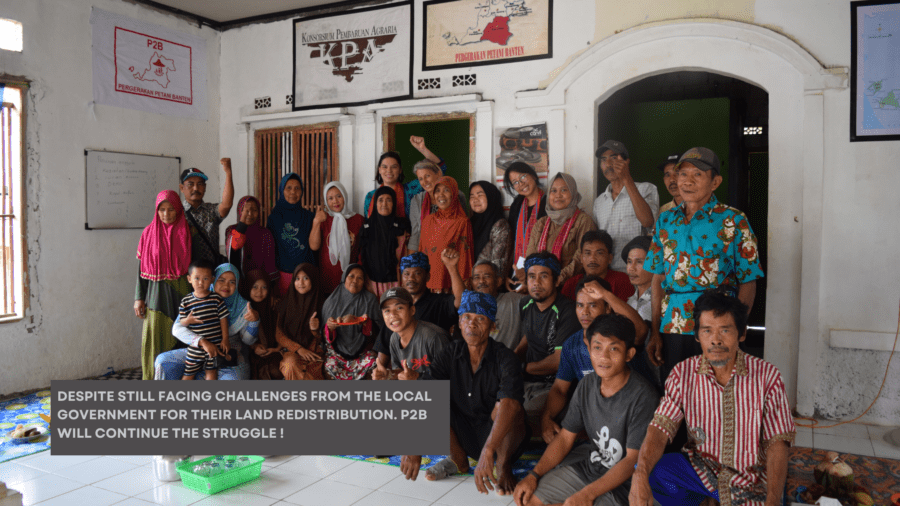

The place is quickly filling up with a warm atmosphere. Women accompanied by children, intrigued to see visitors, are followed by men, and all take seats on the floor. They stare at us with smiling faces. Earlier in the morning, we had left the busy streets of Jakarta and driven several hours through Banten province to reach the village of Gunung Anten. We were invited there by the Consortium for Agrarian Reform (KPA) – an RRI collaborator – to learn further about the genuine implementation of the Agrarian Reform in Indonesia. This settlement is the home of the Banten peasant organization P2B, which is leading a land struggle.

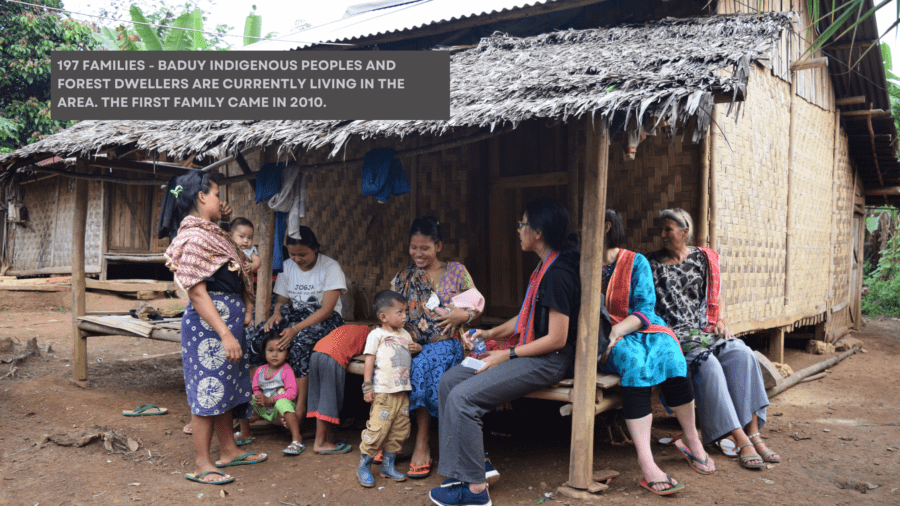

P2B members are reclaiming land in an ex-concession area. They represent 197 families, Baduy Indigenous Peoples, and forest dwellers, who occupy 200 hectares in a former rubber plantation run by PT Bantam which extends over 1,100 hectares. With the support of the Consortium for Agrarian Reform (KPA), of whom P2B is a member organization, the reclaimed area has been mapped out and registered with the government as priority land for redistribution under the Agrarian Reform program. But this has been a long process and the fight is not over yet.

The struggle started in 1989. A man named Sawari told us that he was cultivating the neglected area with fruit trees and already had a land use permit (SPPT). However, in 2007, the permit was revoked, and the residents were evicted by the plantation company.

“In 2007, I appealed to the plantation people, and I was promised seven hectares of land, but it did not exist,” said Sawari, a P2B member. “In 2010, the farmers were interrogated by the police, and our farm was affected. In fact, four people from the community were imprisoned in 2013 for four months. After that, we formed the Banten farmer movement—P2B.”

During the visit, we walked through the surrounding forest to the land being reclaimed. The community showed us how they manage the land that was previously used as a rubber plantation: by growing a variety of crops such as bananas, coffee, red ginger, aromatic ginger, peppers, pineapples, soursop, and a unique sugarcane plant known as “terubuk” (Saccharum edule).

In the evening, we gathered with people telling us stories of fear and courage, struggle and resistance, and arrest and detention.

“I was one of the first few people to be here. On the night of January 12, 2010, I was afraid because our hut was burned. Thugs and police came here, and I was scared to the point of defecating,” recalls a local woman named Aryunah. “I was with my 9-year-old son, and we were told to leave because there would be thugs coming to chase us away.”

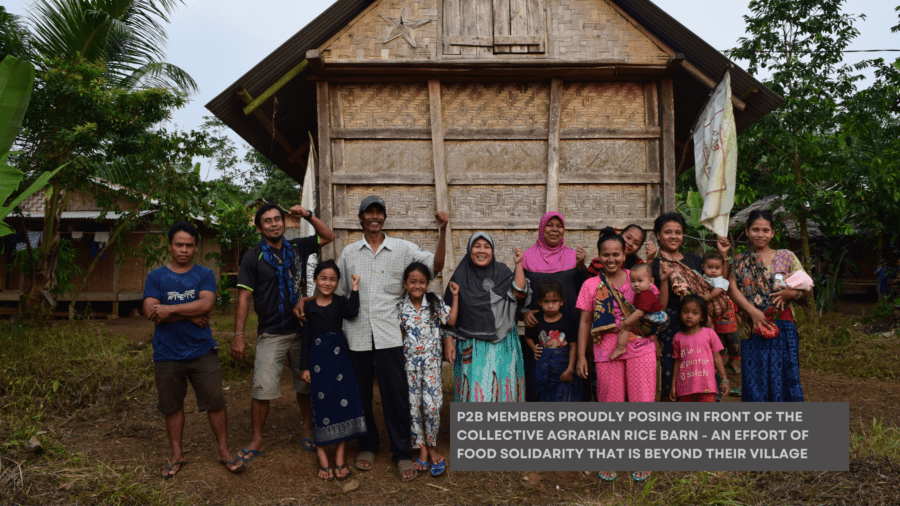

This was before the people started to mobilize under the P2B organization. Since then, KPA has helped strengthen P2B by implementing a progressive agrarian reform model at the village level, referred to as DAMARA, and providing paralegal training for community members. This contributed to building spirit and cohesion in P2B. While individual plots of land are being cultivated, P2B members also work together on a collective plot of land. This is how members are financing the organization and how they managed to build the P2B secretariat where our meeting is taking place, and which also serves as a community training center. In 2020, RRI contributed to KPA’s urban-rural food solidarity work through our COVID Strategic Response Mechanism.

This is a small building, but a big symbol of resistance. “At the time, I was offered big money to stop the construction work,” recalls Pak Abay, a P2B leader. “But I refused it. As children and spouses of our leaders should not suffer because of the head of the family’s engagement.” The collective land also supports those dedicating their time to leading the P2B struggle.

Under the Agrarian Reform, collective land ownership in Indonesia is not yet recognized and the National Land Agency only issues individual certificates. KPA has been trying to register land under peasant organizations’ legal entities, but the government only grants temporary land use permits and not land titles. Despite this legal limitation, collective governance of land is being practiced by peasant organizations. Where the Agrarian Reform is driven by the people through a bottom-up approach, and the land to be redistributed is occupied by strong peasant organizations and clearly documented by KPA as a land prioritized by the people (LPRA), land management is based on joint decision-making. In some instances, members have even entrusted their individual land certificates to the head of their peasant organization, to ensure that no land transaction takes place.

Under the DAMARA, P2B has set up the Agrarian Barn where peasants store a portion of their rice harvest to help those in need within the community. But this solidarity goes far beyond their village. During the Covid-19 pandemic, P2B members sent rice to Jakarta to feed the unemployed. This is part of the KPA-led broader movement for food sovereignty, building solidarity across peasant organizations, Indigenous Peoples, and labor unions.

The community hopes that they will soon receive recognition of their rights to live and cultivate the land with their families without fear or intimidation. “I have no place to return to. I have no land other than what is here. I want to be here until I am successful. I want better for my children. We started the struggle from scratch—we can’t abandon it even if this has not worked out yet,” said Mrs. Mimin, a local resident.

These 200 hectares were expected to be redistributed in 2022, as the P2B claim has been registered as a priority area at the central government level. But the local government also wants a share of the same land, and this competing demand is slowing the process. P2B will continue the struggle.

Unfortunately, women and girls are not yet invited to react on the leadership issue. But a glow is shining in some young girls’ eyes, which could turn into a fire for a bigger struggle for gender justice and land rights recognition.

And it’s anticipated that young people will eventually need to take over the leadership of the organization.

“I want to become a leader, and I can improve my capacities,” said Nana, a young man from the Gunung Anten village. “But will I have enough courage and strength to resist? Would I be able to refuse money as Pak Abay did?”