Creating Prosperity For Indigenous, Local And Afro-Descendent Communities

My Course

Introduction

In this module we’ll learn together by exploring the diverse perspectives, voices, and experiences that shape our collective understanding of livelihoods.

You will reflect on your community’s values and visions for prosperity and well-being. We’ll describe sustainable livelihoods in both theory and practice, and begin to map out what capitals or assets (what people use to gain a living) exist in your territory and communities. In this module we’ll also start cultivating a foundation of trust and mutual understanding through exploring innovative livelihood initiatives together.

What are Livelihoods?

The definition of Livelihoods can vary depending on the community, culture, values or context you’re living or working in. To some it is simply the way people provide for their subsistence, to others, livelihoods is a part of their identity, or it could be just a job. It could also mean creating a business or a larger collective enterprise with your community.

Within the RRI coalition and our networks, we’ve been discussing sustainable livelihoods, self-determined livelihoods, or livelihoods security to mean local peoples’ ability to meet immediate needs and provide a viable future for generations to come, thus affecting their capacity to pursue other goals and priorities, including advocacy for, and defense of, their land rights. At the same time, land tenure security shapes communities’ livelihood opportunities, and the possibility of just and equitable relationships within society – like nearby communities, governments or companies.

Intro to Livelihoods

From the book: Livelihoods and Territorial Innovation for the Strengthening of Community Harmony (page 21):

“The activities carried out by households depend on their livelihoods (what we have), understood as the resources used by domestic groups to be able to live from day to day and achieve their immediate future purposes. The livelihoods that households bring into play can be individual knowledge and skills (human capital), land and water (natural capital), savings and infrastructure (financial and physical capital respectively), as well as collaborative relationships between households and communities, both formal and informal, that help in the projects being carried out (social capital).

Families combine the livelihoods available to them through a set of activities that we call livelihood strategies (what we are able to do). This livelihood strategy allows the family to satisfy, or not, its immediate needs, such as food, clothing, housing, education, health, among others. In the same way, families seek to achieve intangible purposes such as healthy, sufficient and autonomous food. Tangible and intangible purposes make up the expected or desired results (what we want to do).”

Case Study: Clean Energy Production with Cassava Waste

The video showcases a sustainable cassava production initiative in Adou du Bata, Benin, where women in a cooperative, led by Nakaya, have transformed their livelihood through circular production methods. The cooperative uses cassava waste to generate biogas, which is then used for processing cassava, significantly reducing their dependence on wood burning and mitigating deforestation. This also helps protect the women’s health who are exposed to burning wood. Additionally, the biogas production generates organic fertilizer, enhancing soil fertility for future cassava cultivation. This circular approach not only boosts the economic activities of the women’s cooperative but also promotes environmental sustainability and improves the health conditions of the women involved in cassava processing

(Video: In Benin, cassava waste to produce clean energy 11 minutes)

Case Study: Indigenous Communities fighting Monoculture and Creating “Bioeconomies” in Brazil’s Amazon

Indigenous communities in Brazil’s Tupi Mosaic are developing economic enterprises that promote forest conservation. “Today’s economic development paradigm in the Amazon is based on single-product economies, such as beef, soy, and palm oil.” However, there are other models for doing business, such as through “traditional Amazon systems have been based on diversity, not monoculture where local and indigenous communities have been taking advantage of a multitude of crops and wild-harvested foods for generations, drawing carefully on different forest types and cultivated areas, and keeping the overall landscape intact.” The value chains that have been developed with the accompaniment of Forest Trends are acaí, artisan products, Brazil nuts, cacao, and a business model for growing native seeds.

Read the following pages of this illustrative report: A New Bioeconomy in the Amazon Rainforest

📖Read pages 17 and 18 to learn about the acai value chain

📖Read pages 21 and 22 to learn about the artisan products

Mapping Livelihood Assets or Capitals

Thinking about your community or territories’ assets or capital (what people use to gain a living) are important first steps to envisioning potential livelihoods for your community or territory.

Assets can be classified into five types:

- Human capital is the part of human resources that is determined by people’s qualities, e.g. personalities, attitudes, aptitudes, skills, knowledge, also their physical, mental and spiritual health.

- Social capital is that part of human resources determined by the relationships people have with others. These relationships may be between family members, friends, workers, communities and organizations.

- Natural capital is made up of the natural resources used by people: air, land, soil, minerals, water, plant and animal life. They provide goods and services, either without people’s influence, (forest wildlife, soil stabilization) or with their active intervention (farm crops, tree plantations). Natural capital can be measured in terms of quantity and quality (acreage, head of cattle, diversity and fertility).

- Physical capital is derived from the resources created by people. These include buildings, roads, transport, drinking-water, electricity, communication systems and equipment and machinery that produce more capital. Physical capital is made up of producer goods and services and consumer goods that are available for people to use.

- Financial capital is a specific and important part of created resources. It comprises the finance available to people in the form of wages, savings, supplies of credit, remittances or pensions. It is often, by definition, poor people’s most limiting asset.

Different people will also access assets in different ways, e.g., through private ownership, collective ownership or as a customary right.

📖Read more about the pillars and capitals of Livelihood: Agrobiodiversity management from a sustainable livelihoods perspective

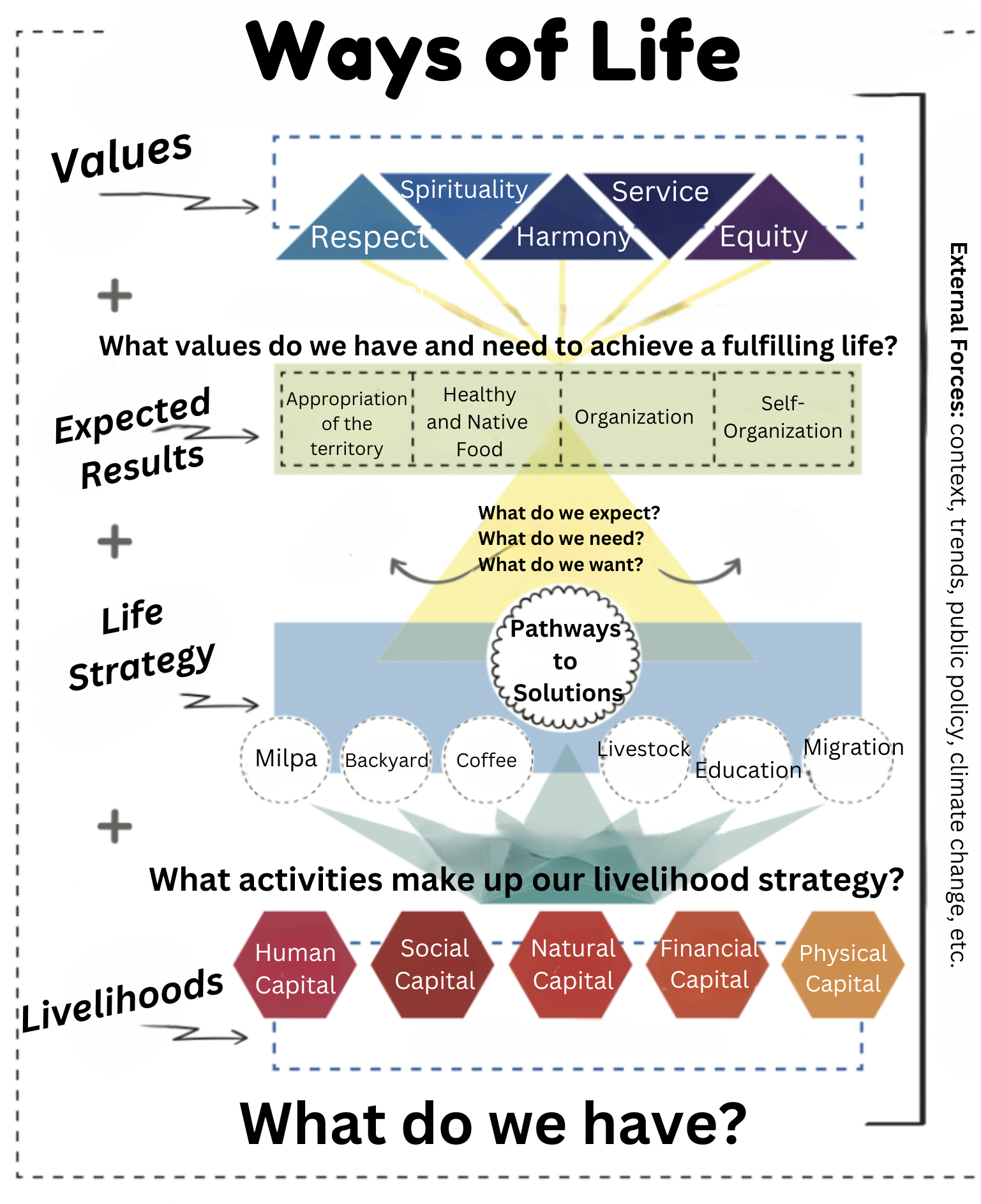

Ways of Life, a values-driven approach to livelihoods

The manual ‘Livelihoods and Territorial Innovation for the Strengthening of Community Harmony’ from the College of the Southern Border in Chiapas, Mexico introduces the concept of “Ways of Life” as a values-driven approach to livelihoods. Ways of Life in this territorial framework is described as “everything that bears fruit around us knowing how to use what has life and what does not have life.”

The authors suggest we ask these questions before we start mapping our community’s capitals: : What do we want to change? What are the values that help the change of strategy?…since these are simply a means to identify the results we expect, and not the end itself. Livelihoods comprise the strategies followed by communities according to their available capitals to satisfy their needs, according to their values. Livelihoods are not static, they are dynamized by territorial innovations that communities constantly put to the test.

📖Read a short excerpt from pages 24, 25, 26 of the manual, for an overview of Ways of Life

Diagram: Ways of Life

Homework

Activities to complete after the first live session.

Approximate time: 1 hour and 30 min

Guiding questions and prompts that encourage discussions on sustainable livelihoods with elders from the community.

Identify the core values and desires of your community, providing a foundation for mapping assets and identifying sustainable livelihoods possibilities.

In the United States: 2445 M Street, NW, Suite 520, Washington, DC 20037

+1 202 470 3900 [email protected]

In Canada: 401-417 Rue Saint-Pierre, Montréal, QC H2Y 2M4

I’d like to receive news about: Community land rights in general | Latest blog posts from RRI | Gender justice in land and forests | Mobilizations and urgent action alerts