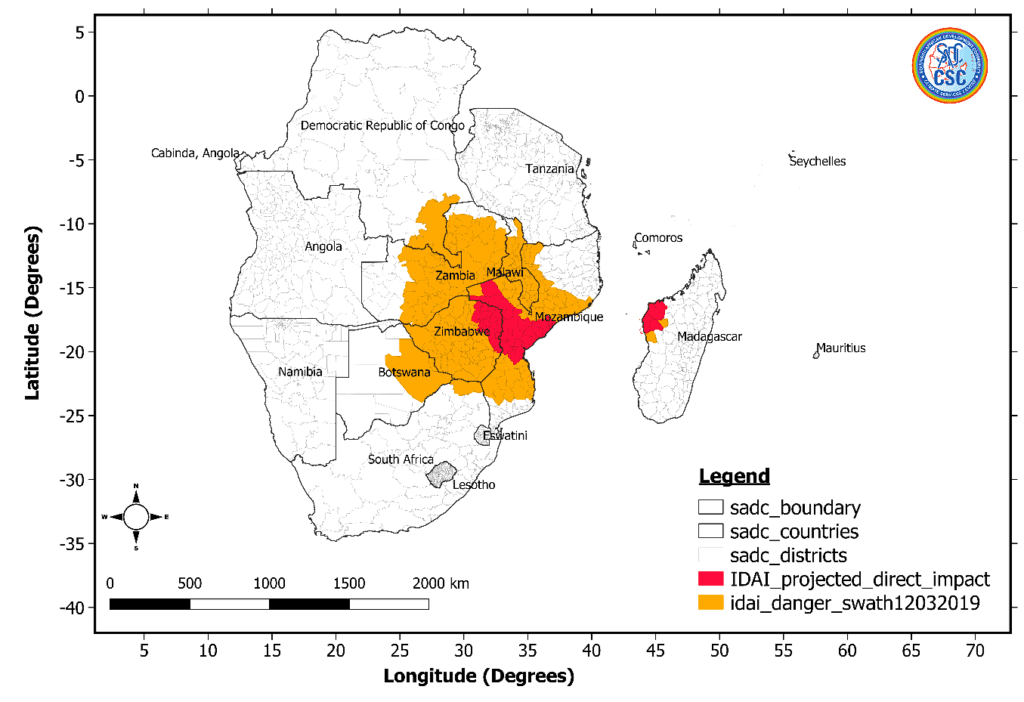

In March this year, Cyclone Idai devastated communities across Malawi, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe, killing over a thousand people. It laid bare governments’ lack of disaster preparedness in the affected countries (Figure 1). The United Nations has stated that Cyclone Idai is possibly the worst ever weather disaster to hit the southern hemisphere, and it won’t be the last. If anything, this disaster has brought home the message that disaster preparedness is inadequate. The design and planning of cities and physical infrastructure should be climate-resilient, taking into account the many important ways in which local community rights and capacities, nature, and nature-based solutions contribute to reducing risks and building resilience. This is particularly pressing as climate change heightens the frequency and magnitude of these extreme weather events, exacerbating the vulnerability of millions of Africans.

The increasingly devastating effects of climate change on local communities

Cyclone Idai revealed the extent to which existing rural and urban physical infrastructure, as well as that which connects cities and countries, was susceptible to severe climate change-induced weather events. As is often the case with disasters of this magnitude, ports, roads, railways, pipelines, and transmission lines were severely damaged, disrupting inter- and intra-national social and economic activities across the three landlocked countries. Damage in the rural areas included loss of houses, commercial buildings, schools, roads, and bridges. Flooding has been severe, especially in the low lying coastal city of Beira and within rural communities in the mountainous region of Chimanimani, where flooded rivers swept away buildings and people. Persistent heavy rains caused mudslides and virtually cut off a small town in eastern Zimbabwe. The worst affected area was the Rusitu communal area at the confluence of the Nyahodi and Rusitu rivers, followed by the Chipinge District (See quote below).

Cyclone storms worsened damage to our houses that had already developed cracks due to an earth tremor in December 2018. A total of 601 mm of rainfall was received in four days. All our crops were wiped out with countless livestock drowned. Floods and winds destroyed businesses, schools, clinics, churches, roads and communications infrastructures. Access to markets, health facilities, and forest compartments where we work was complicated and challenging; even our production orders declined sharply.

—Statement from Ngungunyana near Mt. Selinda in Eastern Zimbabwe

As the affected countries move from coping to recovery, it is clear that a new approach to designing, planning, and building physical infrastructure is needed to reduce vulnerability.

Embracing new technology, innovation, and recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ and communities’ rights as solutions to climate-related disasters

The concept of resilience demands that nations design, plan, and construct physical infrastructure that can withstand the increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events. At its core, resilience is the ability of individuals, communities, organizations, or countries exposed to disasters and underlying vulnerabilities to anticipate, reduce the impact of, cope with, and recover from the effects of disasters. While many current challenges need to be addressed, governments also need to be proactive so that they can anticipate emerging challenges and mitigate associated risks.

Embracing new technology and innovation is key to developing and adopting infrastructure that is resilient to climate change, and this will require working across sectors and disciplines. Climate-resilient infrastructure is planned, designed, built, and operated in a way that anticipates, mitigates, and adapts to the changing climate. Its planning and development must go beyond simple “climate-proofing” to account for the numerous ways in which nature can help reduce risks and build resilience, especially if managed with climate change in mind. Forests and wetlands that act to slow down or store floodwaters and coastal mangroves and reefs that absorb deadly storm surge are just some of the functions that nature provides that must be central to resilience planning for infrastructure moving forward.

Reducing vulnerability of local communities—who often bear the brunt of extreme weather—requires investment in local capacity such as access to knowledge and information, having a longer-term perspective to rethink things like physical planning, and empowering communities to actively participate in decisions and collective actions. Since government entities can only take actions consistent with their capacity level, they must be adequately financed, have requisite levels of human capacity, and receive access to information and technology.

Secure and equitable land and resource rights equip poor and marginalized communities to survive disasters and build local resilience, much as insecure land tenure can be a potential source of vulnerability. These rights help shape access to and sustainable management of natural resources and aid communities in recovery after disasters. Clear rights enable the settlement of individuals and communities away from areas physically exposed to disasters, such as steep hillsides and close to river banks, as happened in Rusitu communal area (See Box 1).

The broader impacts of climate change on infrastructure are being recognized in Africa. The reduced capacity of hydropower dams, shortened road maintenance cycles, and disruption to critical services due to damaged bridges and buildings can have major impacts on a country’s economy and wellbeing of its people. The transboundary nature of much of the infrastructure damaged by Cyclone Idai, including pipelines and roads, illustrates that a regional or transboundary approach to climate resilient infrastructure is required for long-term resilience and securing viable energy networks and transportation systems for goods and people. The World Bank, the African Development Bank, and the Economic Commission for Africa have launched the Climate Resilient Investment Facility (AFRI-RES) with the aim of strengthening African capacity to integrate climate resilience into the design of energy, water, agriculture and transport investments. To reduce the vulnerability of local communities to extreme weather events, the AFRI-RES must specifically include strengthening the capacity and respecting the knowledge of local communities, rather than just project developers and formal institutions, to integrate climate resilience into the planning, design, and implementation of physical infrastructure.

Greater attention needs to be given to rural populations and their vulnerability to extreme weather events. It is critical that future infrastructure go beyond the models of the past designed for a climate that no longer exists, and holistically plan at a landscape scale, not just for climate-proofing concrete, but truly accounting for the natural infrastructure and community capacity that are critical to long-term resilience.

About the author: Yemi Katerere, an RRI Fellow, also works with the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and coordinates the African Ecological Futures Programme, a partnership with the African Development Bank, the UN Environment Programme, and the Luc Hofmann Institute.

Interested in receiving notifications about new blog posts? Subscribe to the RRI blog now to get new posts delivered right to your inbox.