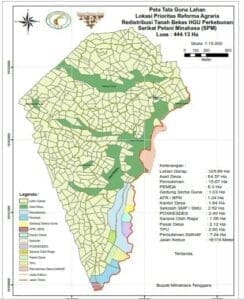

In Southeast Minahasa District, North Sulawesi, 444 hectares of land were returned to the Peasant Union, benefitting 491 people in Mangkit village. For over 30 years, the Mangkit have been cultivating the disputed land occupied by PT Asiatik, a coconut plantation company that eventually split into three different companies.

Why has Agrarian Reform not been effective so far?

Thus far, the government has focused on the formalization aspect of agrarian reform, issuing certificates for those occupying undisputed land. This includes poor farmers who have been resettled under the official transmigration program and given a plot of land for agriculture.

But this is different from KPA’s goal: land redistribution. Land redistribution is about returning disputed land claimed by Indigenous Peoples, local communities, and others. It covers recognizing communities located inside forests that are currently considered “illegal” by the government despite evidence that local peoples are the best guardians of these natural resources, as well as returning agricultural land that has been taken from farmers to develop industrial plantations, infrastructures, and other projects. For KPA, land equity can only be achieved if agrarian reform is implemented to solve conflicts by redistributing land to the people, including those who have lived on and managed their lands for generations. The Agrarian Reform program targets 9 million hectares of land: 4.5 million for land redistribution and 4.5 million for formalization of land ownership. Land to be redistributed is to originate from forest area for 4.1 million hectares and from unused or expired concessions granted to companies for the remaining .4 million. Unfortunately, this part of the agrarian reform program has seen very little progress. In five years, land redistribution is still lagging behind, with less than 1 percent of the target 4.1 million hectares of forestland recognized.

One reason is that the government is still sticking to the “clean and clear principle,” which requires that any land redistributed should be free from competing claims. Another reason is that in some provinces like Java and Bali, where forest cover is under 30 percent, the government does not want to release land from forest areas. The only option offered is social forestry, granting local communities management rights to state forestlands for 35 years. But social forestry is not an adequate scheme to solve the problem of the villages “illegally” located in forest area. This also explains why unclaimed land prioritized by the government is often inadequate for farming. For instance, in one case in Aceh, the redistributed land is located in the middle of a river.

KPA Struggle for a Genuine Agrarian Reform

To counter this top-down approach, KPA has been pushing for a bottom-up approach (referred to as LPRA, priority location for agrarian reform), where land to be redistributed is prioritized by the people themselves. This important work of KPA has been supported by the Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI) and more recently by the International Land and Forest Tenure Facility.

Of course, claimed lands have often been the object of disputes that pit communities against private or public companies, or the government. But a genuine agrarian reform is about solving such conflicts by considering the interests of marginalized peoples.

So far, KPA has consolidated priority locations for Agrarian Reform in 533 villages covering over 650,000 hectares, which would benefit more than 192,000 peasant families (with over 12,000 female headed households) in 20 provinces. Out of these, the government has now prioritized 145 villages with 115,000 hectares. Yet only 785 hectares of land prioritized by the people has been redistributed.

Land Redistribution in Mangkit Village

There are however some examples of success, including the priority area claimed by the people in Mangkit. The Minahasa Peasant Union (Serikat Petani Minahasa, SPM), a local peasant organization that was supported by KPA, achieved recognition of the Mangkit’s land in October 2019 and helped ensure that people were ready to manage their lands with a strong collective governance system.