In February 2016, villagers in Sonakhan in Chhattisgarh state in India learned from national newspapers that over 6 square kilometers of their customary land had been sold to a gold mine in an international auction. None of the villagers who lived in the area had been consulted. No one spoke with the village council. There had been no discussion about compensation. Yet, estimates show that privatizing the land for mining will impact the livelihoods of people in at least 24 villages. Since learning of the international auction, villagers have been protesting to state officials for the reversal of the decision. Given India’s immense size, many people outside of Sonakhan are likely unaware of this ongoing fight, but Land Conflict Watch is tracking the development of this conflict and many others in order to amplify the voices of local peoples demanding recognition of their rights. An online platform which maps land conflicts across India, Land Conflict Watch serves a crucial role by documenting land conflicts both large and small, supporting evidence-based policy, and encouraging government accountability.

Co-founded by journalists Ankur Paliwal and Kumar Sambhav Shrivastava in 2016, Land Conflict Watch has documented over 600 conflicts across India in the last two years. The majority of these conflicts are on community-owned rather than privately-owned land. “About 75 percent of land conflicts arise from development and industrialization processes with infrastructure projects being the single largest cause of conflicts. In contrast to accepted wisdom, the majority of land conflicts in India are related to common rather than private lands—close to two-thirds of all conflicts. This is because land tenure in common lands is less likely to be legally recognized than in private lands. Despite lack of rights recognition on common lands being among the greatest causes of conflicts, they have not received adequate attention so far,” says Shrivastava. Given that India is the seventh largest country in the world with a population of 1.3 billion people, it is not surprising that land conflicts that affect more remote communities and Indigenous Peoples rarely gain national or international recognition. Land Conflict Watch tracks these cases in order to make them more visible and actionable for journalists, researchers, and policymakers.

Verification and Evidence-Based Reporting

Land Conflict Watch has an extensive data verification process in order to ascertain that the information presented is accurate. Paliwal, Shrivastava, and their team of about 30 researchers hailing from across India record and document land conflicts identified in regional newspapers and alternative media, through firsthand accounts gathered via a vast NGO network, and through informal community networks who track conflicts or are directly affected by them. Following this initial step of identification, every data point is cross-checked against other documents such as police reports, memos submitted to local authorities by communities, and transcripts of public consultations of development projects. Where there are no documents, researchers reach out to communities and other people on the ground.

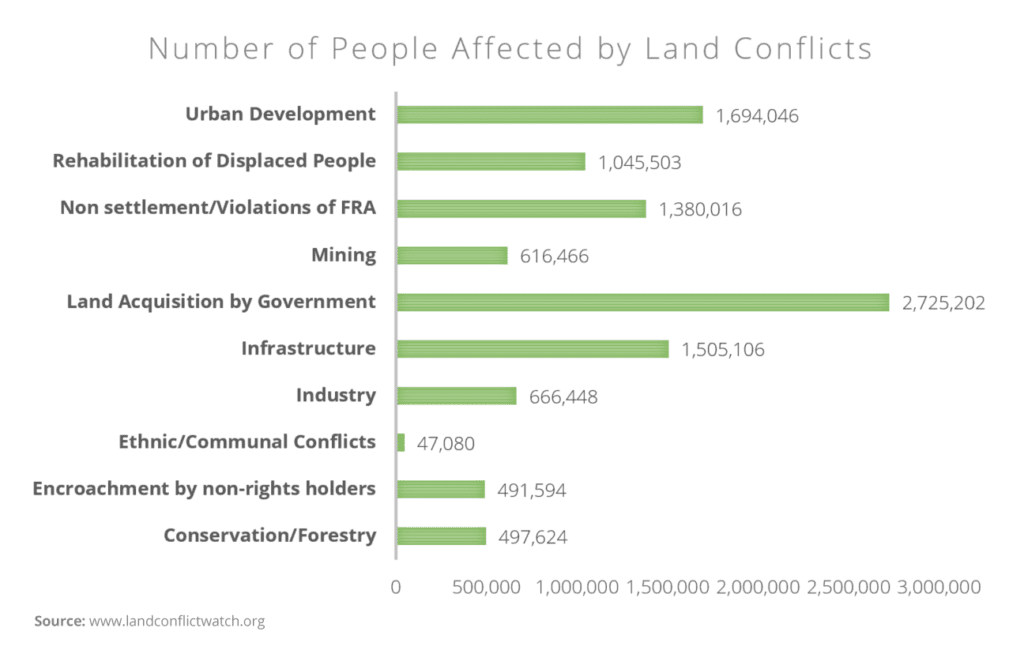

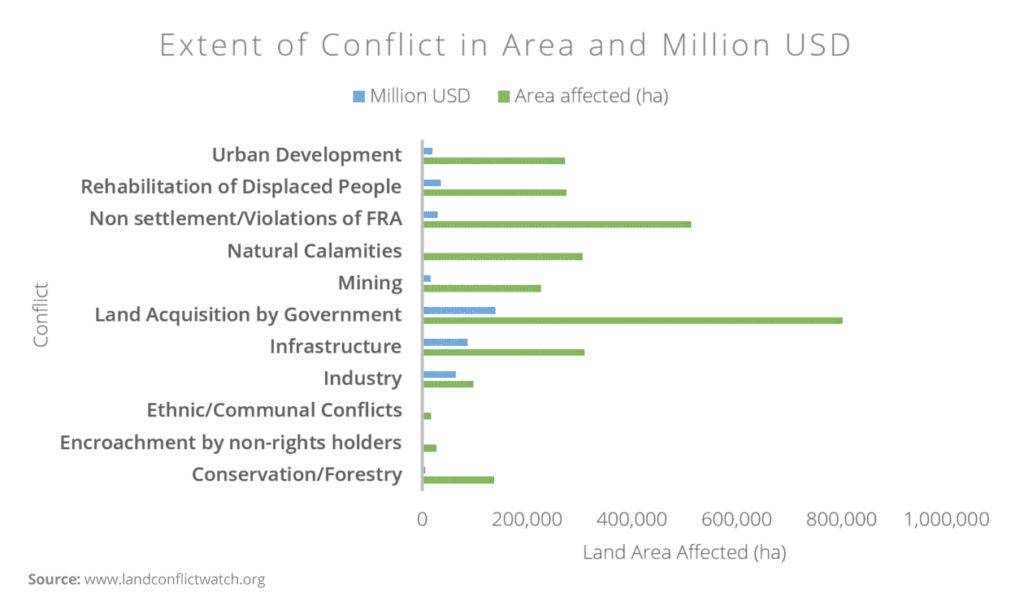

The platform documents conflicts that range from encroachment by non-rights holders to ethnic/communal conflicts to natural calamities and land acquisition by government; and measures instances of conflict through the number of people affected, the land area in question, and the investment affected. For example, presently there are 47 mining conflicts affecting 616,466 people, with 225,843 hectares of land and investments worth ₹106,859 crore (US$15.6 billion) affected. In determining the economic value of conflicts, researchers use information on investments already prvoided by governments or the private sector, projected investments from projects, and proposed investments—all information that is publicly available but not otherwise collected and shared.

Accountability

Documentation is only a first step in helping local communities secure land rights. Through the rigorous verification process, Land Conflict Watch increases the accountability of government officials and government policy by tracking violations of laws such as the Forest Rights Act (FRA). Enacted in 2006, the FRA—officially known as The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act—seeks to right a historical injustice by recognizing forest dwellers’ rights over their forest resources. A 2015 report of the Rights and Resources Initiative suggests that if the FRA was fully implemented it could lead to recognition of the rights of at least 150 million forest-dwelling people over 40 million hectares of forestland in more than 170,000 villages. The FRA could increase the annual income from non-timber forest products (NTFPs) of forest dwellers by 20 to 40 percent.

On a local level, Land Conflict Watch data gives local communities evidence of conflict and can help to support the claims of villagers such as those in Sonakhan as they face powerful private developers, local government officials, or both.

Globally, this data has been used by international media organizations and academic institutions to chronicle land conflicts. A 2016 RRI and Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) analysis of land disputes and stalled investments found that a quarter of stalled high-value projects in India came as a result of land conflicts accounting for ₹1,926.2 billion or US$28.8 billion. Indian and international journalists have also used Land Conflict Watch’s data to uncover new stories about land rights and to substantiate their stories about land and development in India. By providing evidence on conflicts, LCW’s growth and success in India mirrors that of similar land conflict tracking services around the world such as Tanahkita in Indonesia and TIMBY (This is My Back Yard) which began in Liberia. Similarly, LCW has helped to document conflict, support communities as they seek legal recognition of their lands, and hold governments accountable in upholding forest rights legislation.

Looking to the future, Paliwal and Shrivastava envision Land Conflict Watch becoming a resource for land conflicts in India that is useful to a variety of stakeholders. “We hope to develop Land Conflict Watch as an agency that specializes in documenting cases related to land, of which conflict is one lens. Land is central to key developmental indicators such as health, economics, and education, and we would like to have a deeper analysis of India’s development going beyond conflict,” said Paliwal.

About the author: Wendy Atieno is the Asia Program Intern at RRI.

Interested in receiving notifications about new blog posts? Subscribe to the RRI blog now to get new posts delivered right to your inbox.